Incentive Structure of Film

Film or Content

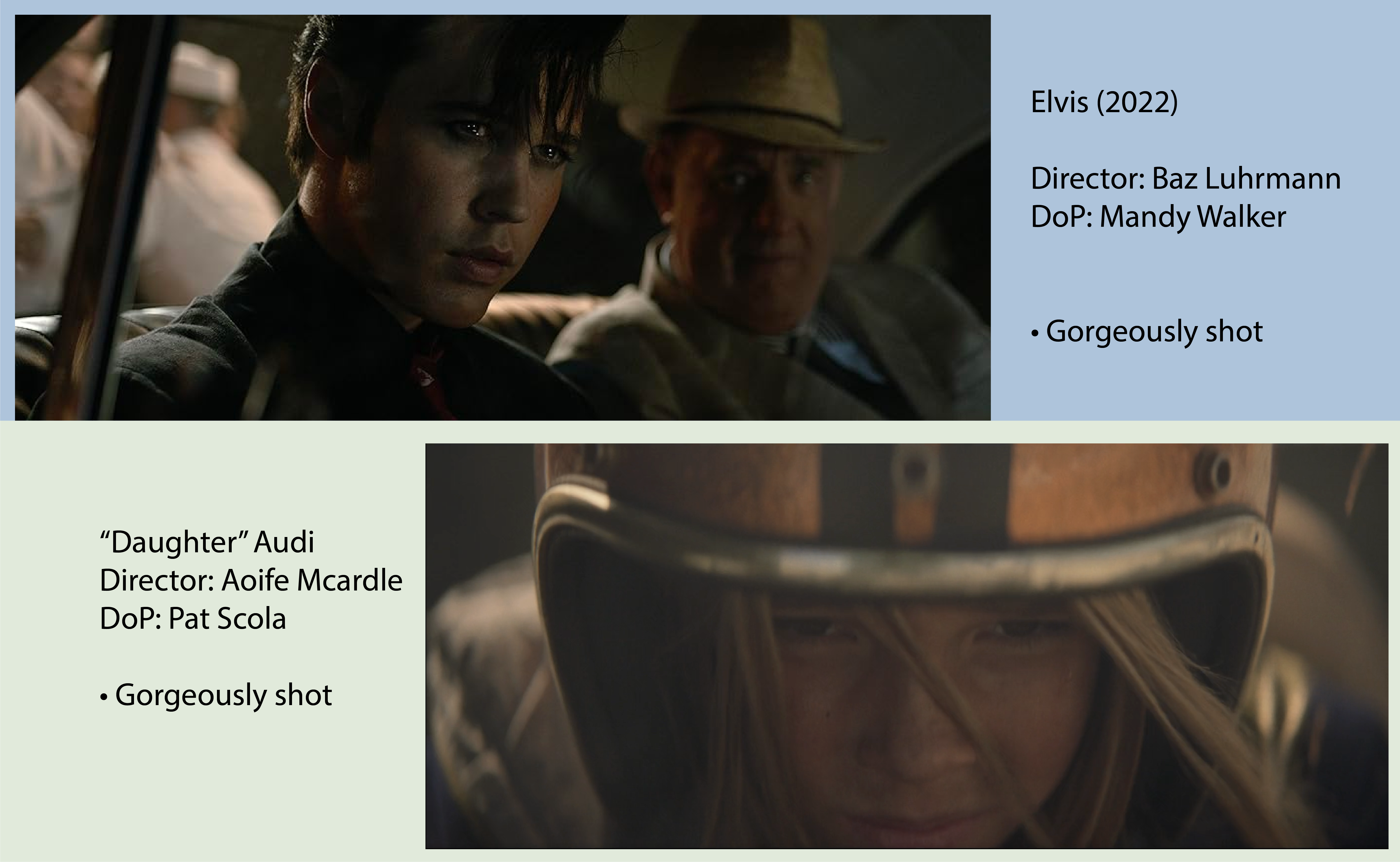

If it looks like a Panavision, shoots like a Panavision, and hums like a Panavision, does that mean it produces motion pictures?

At what point does a motion picture film differ from video content shot on like-tools? If there’s an A-list actor in the frame, what then? What if all, or most of the ingredients are in both? Where does high quality content begin, and film end?

If both products feature a star, multi-plane lighting, a well-placed leko, scenery on wheels, and a background cast running sixties to a stopwatch— where does one differ from the other?

When is a film, not-not?

If you switch, mediums, and compare two trays of ham. Both cooked by the same protocol and with mostly the same tools.

-

One cooked by a cook, who is paid by a day rate, is sourced by a cook staffing agency, and has a short term calendar that is highly sought after.

-

The other ham is made by a cook, also sought after. But the results of their ham are much more consequential. You could say they own stock in the restaurant, and the reception of this ham will determine their standing with restaurant investors and their future.

Does either ham taste better or worse?

Truthfully, it’s a moot question. But it does raise an interesting dynamic worth exploring, what role does risk play in the parsing of incentive?

Incentive Structure of Traditional Film

The incentive structure is a key point of differentiation often overlooked when comparing motion mediums. It’s not as tactile or as easy to put your finger on as– the glass last years Oscars were shot on.

Audiences may not realize it, but they can likely intuit if a picture was made for theaters, or made to thumbnail a display page.

At it’s most reducible element, a motion picture is a visual story made to be seen in theaters.

- That is it must be seen in theater to earn its value.

This is the integral difference between a traditional film, and anything else on a TV box. Assuming exhibition goes well, this works out well for the filmmaker, who in exchange for their prowess are rewarded by the market w/ accolades & dollars.

The audience in exchange for a negligible amount of money— receives spectacle in the form of visual escapism.

Traditional Motion Pictures

Primary Income Driver

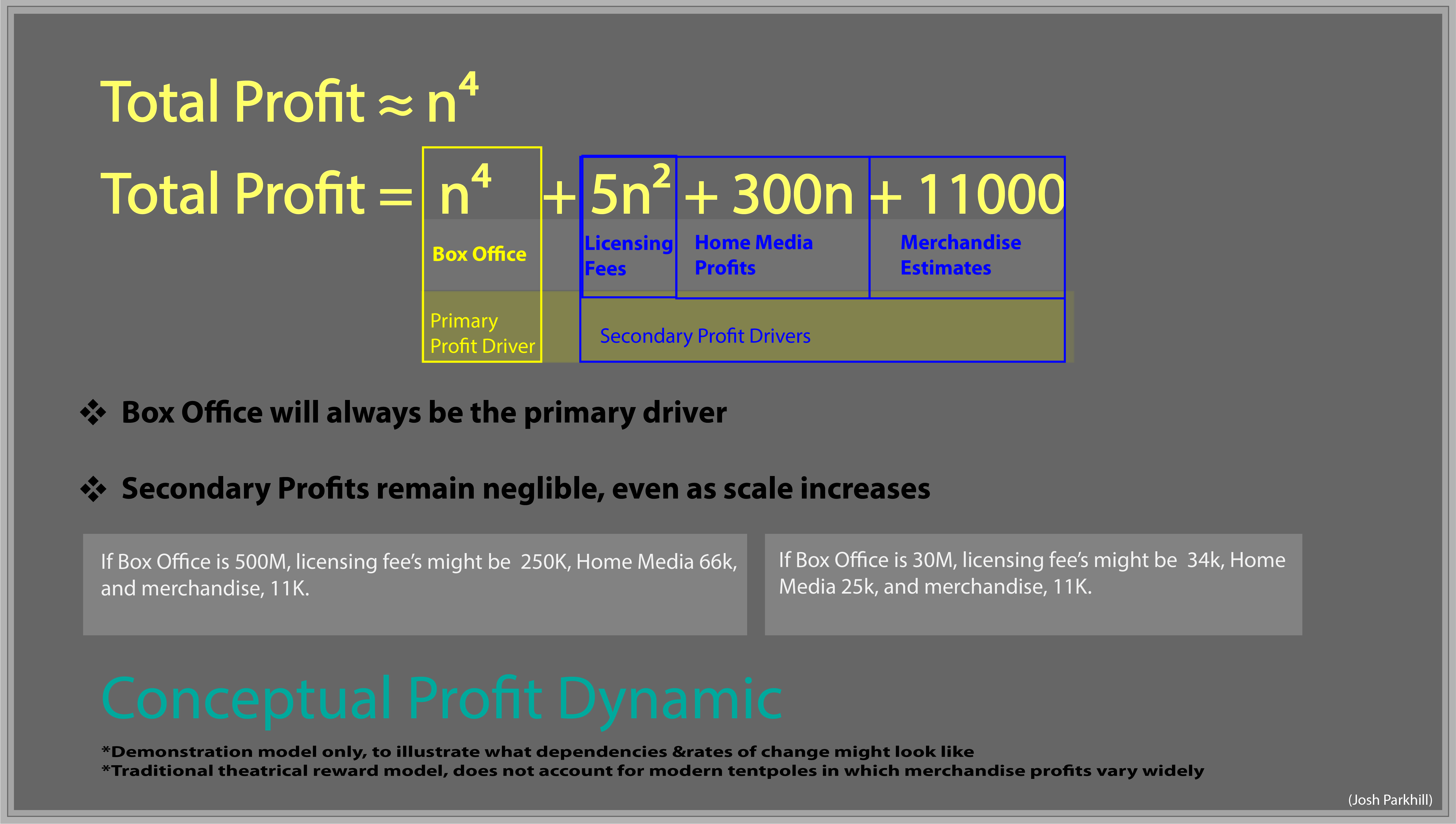

Traditionally, a theatrical film earns its existence through exhibition. Without a successful exhibition it doesn’t make its money back. This has been true since it’s inception, and remains mostly true today. This is effectively the same model used by Broadway, Vegas, and any live performance exhibition.

- Exhibition is a pictures primary means of revenue.

- incentive ≈ exhibition - (COST)

The difference between pictures and live performance, one can be duplicated and parsed out at scale. note: the ability to distribute at scale, means you must deliver something that is scale worthy.

Secondary Streams

In the traditional profit scheme of theatrical movies, secondary streams are(or were) always nominal compared to box office. In fact, secondary streams are predicated upon box office success, mathematically. Merchandising, home media, licensing, broadcast agreements all stand to bring in meaningful secondary revenue.

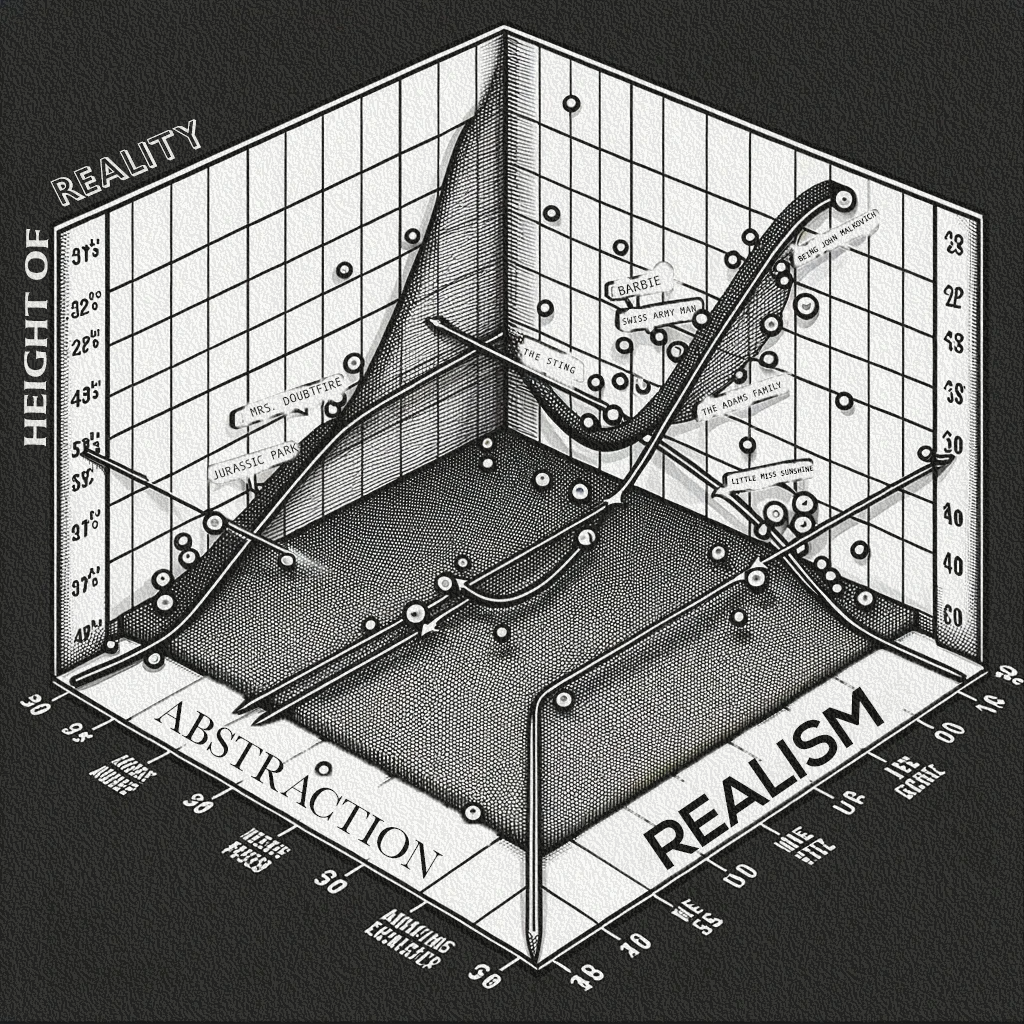

Below is an illustration, that demonstrates the relationships between secondary streams have to primary revenue, assuming the following rates of change.

- Box Office = Primary High Exponential Growth

- Licensing = Quadratic Support Dependent

- Home = Linear Peripheral Revenue

- Merchandise estimated at an assumed flat rate. (note: this doesn’t account for today’s modern tent pole films.)

The general rule of thumb here is, the sum of secondary income exists in relationship to the much larger amount of primary income.

Today, this scheme hasn’t shifted as a radically as some opinions may have you believe, but merchandise is less easy to pigeonhole and licensing fees are relative to specific studios and their overall business design.

Merchandise

Whereas merchandise profits can vary widely in return, they still depend on the picture’s success to do so. This is true even in pre-_millennium_ examples, such as Batman(1989) and Star Wars(1977-1999). If the picture’s hadn’t been successful, than neither would be merchandise. The takeaway here is exhibition and audience turnout are the meaningful driver in the equation.

Core Requirements for Exhibition

It’s advisable, but NOT REQUIRED that a picture have the following.

- PR Buzz

- A Marketing and/or Ad Campaign

- Director Brand Image

- A Compelling Premise

- Budget Pzazz

There are examples of successful exhibitions foregoing some or all of the above elements. However, there are a few things a film MUST always have to be a box office success.

1. The Picture must have a Star. 2. The Picture must entail risk that can only be justified by exhibition.

Without those ingredients you DO NOT have a motion picture in the traditional sense.

What you likely have is a TV movie, an internet movie, or some other form of mixed medium branded content.

Briefly

Why a Star?

See rule 2. A star is the bare minimum of what’s required to bring in enough-of an audience to recoup cost. There are no examples (I’m aware of) in which a movie has NO headline star and has a successful box office outing. If there are, they are outliers, even Rocky had Carl Weathers. Without a star the filmmakers are effectively playing make believe in the woods with a camera. The product is not something the market will entertain.

Risk justified through Exhibition

The way a logline summarizes the motivation for a protagonist, cash on the line summarizes the interest of the backers. The prospect of risk versus reward functions as a driving force that encompasses the production driving it all the way to distribution. This is not unlike dark matter– a sense of risk is there, it can be felt, but its not necessarily tangible. The filmmakers, the producers, the director, are all operating with that prospect in mind.

This makes for risk compelled timelines, and risk compelled decision making, is this different from other risk intensive production medium?

It is, because the actions and decisions made amount to a bet. A bet that can only be returned via theatrical exhibition. Filling seats is the only measure of success. It’s also what makes the medium incredibly unique, that need for return-factor is built into what takes place on set and what you see on screen. In an age where we are inundated with video, and the notion anyone can be a YouTube, it’s nice to remember film is brought forth from very unique circumstances.

And, like gambling, filmmaking can be approached calm & logically. But. At a certain point you are putting money down on a bet, and there are no sure things. A horse can drop from first to last in the final stretch. Twentieth-Century Fox literally bet the farm with Titanic (1998), which, if a flop, as many predicted, would result in bankruptcy for the studio. When the picture did debut- the inversion of anxiety to euphoria experienced by the decision-makers at Fox must have felt like nothing short of a jackpot.

picking the right horse to bet on

picking the right horse to bet on

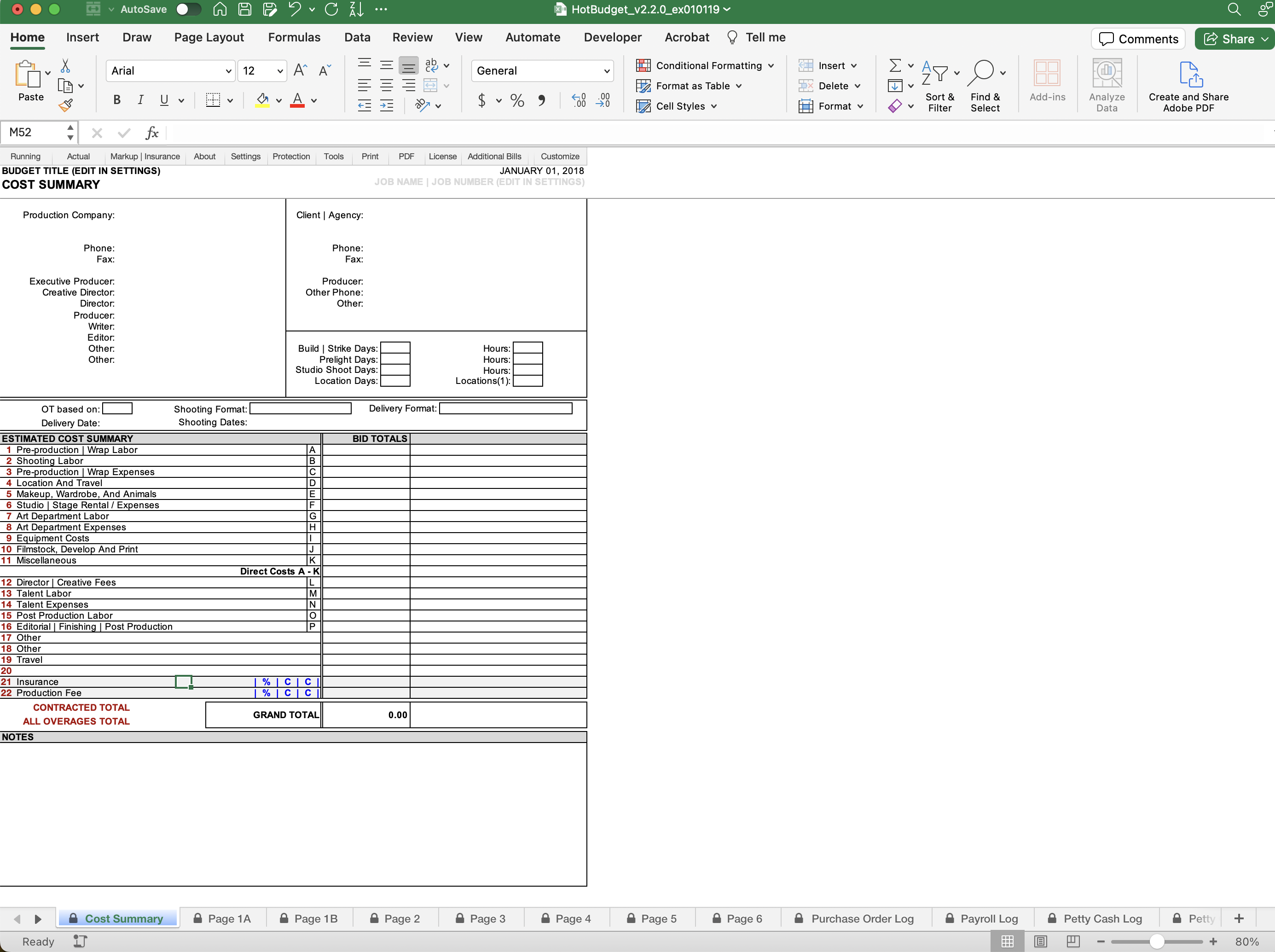

Non-Theatrical Movies: a diffusion of incentives

It’s not TV. It’s TV Movies.

Just because a movie is shown in theaters, that doesn’t necessarily make it a theatrical movie. It could be a TV movie, shown in theaters for whatever reason. In part it comes down to- how was it designed to earn revenue? But also, what’s the risk dynamic at play? In the best scenarios risk is actualized through realization of vision.

Movies like Scorsese’s The Irishman, or Baumbach’s White Noise are technically TV Movies. They weren’t designed to generate their money back through the Box Office. They were made to bring in, or keep streaming subscriptions. Both Scorsese and Baumbach are box-office tried and tested directors, and the products they created very much smelled like real theatrical movies. Moreover, there were external & internal pressures to perform well critically, even though revenue wasn’t on the line per say, rather this was a risk of hubris.

But if a TV Movie is anything— it’s a movie, with the elements of risk removed. No one typically know’s the name of a director. No one typically cares. There’s no pressure to make back the money spent. In some ways, the job is done before it’s even started.

A Not-So Great Example

The Take (2016) starring Idris Elba, produced by Anonymous Content had a reported production cost of 4 million, and presumably low-to-no marketing spend.

When it went to theaters, it cleared 50K domestically, and 15 million worldwide. A notably small amount for an action movie, but clearly surpassing cost nonetheless. Soon after, it was flipped to streaming, to both Amazon and Netflix. It’s reasonable to assume for a fee somewhere in the low million/s.

This movie is by all means of measurement a financial theatrical success.

But what was really at risk here? 4 million is a low bar to clear, certainly with the star-studded power of Idris Elba.

One only needs to watch the opening sequence of this movie to realize it is remarkable only in how unremarkable it is. Baseline camera work, an obvious production setup and camera crop, and a push-in that reads more as uninspired than drama. To me this feels like what happens when there’s no bar to clear. It feels like a movie that lacks that intangible something. The critical mass that occurs when you sprinkle in marketing, sweat equity, hollywood headliners, and stakes. All ingredients seen in great movies.

Can an entire movie be filler? Where’s the carrot, where’s the stick?

A thought experiment—

What if Coppola had been tasked with making ‘The Godfather’ as a TV movie instead? What if all the stress and risk of the production were removed? And along with that, the meticulous oversight and feedback process that the production is famous for. With the scale + beauty + risk of exhibition gone, what would the result be?

Godfather: The TV Movie

Godfather: The TV Movie

Modern Cinema

Cinema is different today. But it’s not that different. Despite the surplus of editorial chatter about super hero movies, and franchises, the paradigms of exhibiting a theatrical film are essentially unchanged. The dynamic of secondary streams is wildly varied, and market conditions are markedly different, but the operational structure of exhibiting a film is the same as it always was.

Before exploring, its worth defining some common terms, in the lenses of incentive structure.

Concepts

- IP

- Franchise

- Spectacle

- Scale

- Theme Park Films

IP & Franchises

IP = (Public Awareness) + (Sales Viability) = Market Fitting IP ≈ Market Fitting a product

For all intensive purposes, IP (intellectual property) brings two distinct tangible_/intangible_ elements to the table.

For all intensive purposes, the value an IP (intellectual property) has, comes from the culmination of two distinct tangible/intangible elements.

- Public Awareness of a property. Is the public aware of this prototype, schema, universe or what-have-you?

- Sales Viability? Is the public willing to spend on said embellishments. This is usually proven through some form of cross domain sales, or public outpouring of support.

Note: A public’s awareness of a property doesn’t necessarily correlate to sales. For instance, the public is aware of the Cuban Missile Crisis. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they will spend money on a film about it.

2nd note: But if you combine the public’s awareness of an event, with their awareness of a branded style of filmmaker, say Christopher Nolan. You have in effect- created in their mind IP they are aware of. Christopher Nolan does the Cuban Missile Crisis.

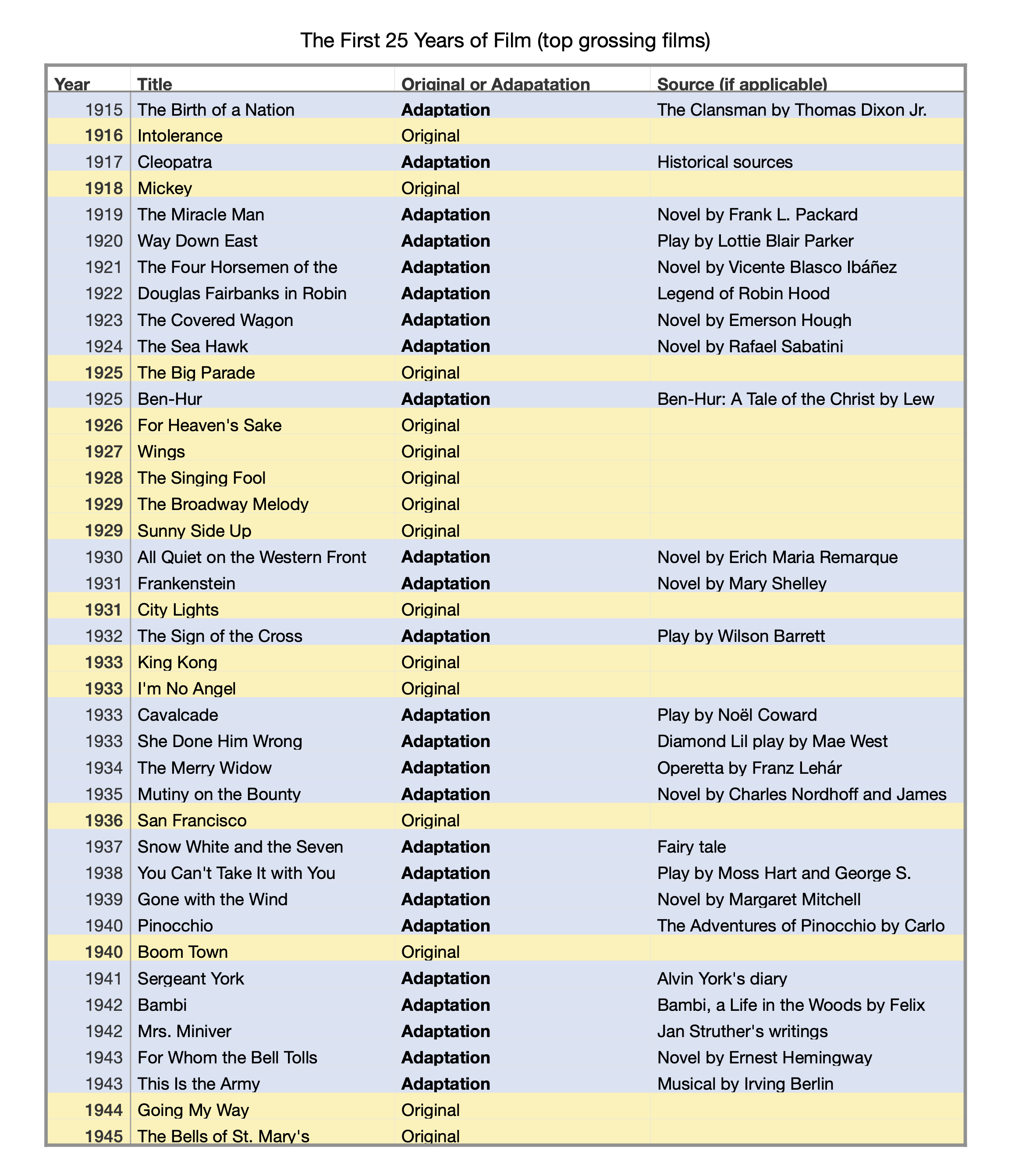

At it’s basis, a studio’s IP proves there is awareness, and pathways towards sales success. This is not a new technique. It’s been used since Hollywood’s debut. Creating pictures based on proven novels, plays, or acclaimed domains has always been the name of the game.

A selection of Hollywood’s top grossing films in it’s first 25 years of theatrical exhibitions, show’s 62% of its films were adaptations. The tendency for studios to use proven IP’s is nothing new, but something old.

25 Years of Film, Adaptation or Original - (Top Grossing Films Wikipedia )

25 Years of Film, Adaptation or Original - (Top Grossing Films Wikipedia )

Franchise = market priming an IP

In addition to the established benefits of using an IP, franchises take this a step further by stretching the viability of a given property. A franchise has the dual mechanism of entertaining an audience in the moment, while wetting their whistle for the next viewing at the same time.

Look to the ending of Batman Begins, for a modern example. At the end of an effectively standalone story, you, the audience are teased with iconic IP to prime you for the next installation. This of course manifested into the end credit scenes trope

This phenomenon isn’t limited to this trope. One could argue that merely installing an entry into a series, hinting at world beyond the scope of plot— is enough to pique the interest of Jonny-ticket-buyer.

- Rocky III primes the audience for Rocky IV.

- F9 primes the audience for FX.

Scale, Spectacle, Theme park

Scale, Spectacle, and Theme Park are sometimes thrown around synonymously.

Theme park films, popularized by Scorsese, are franchise films with a myriad amount of secondary revenue streams, which notably includes theme park rides.

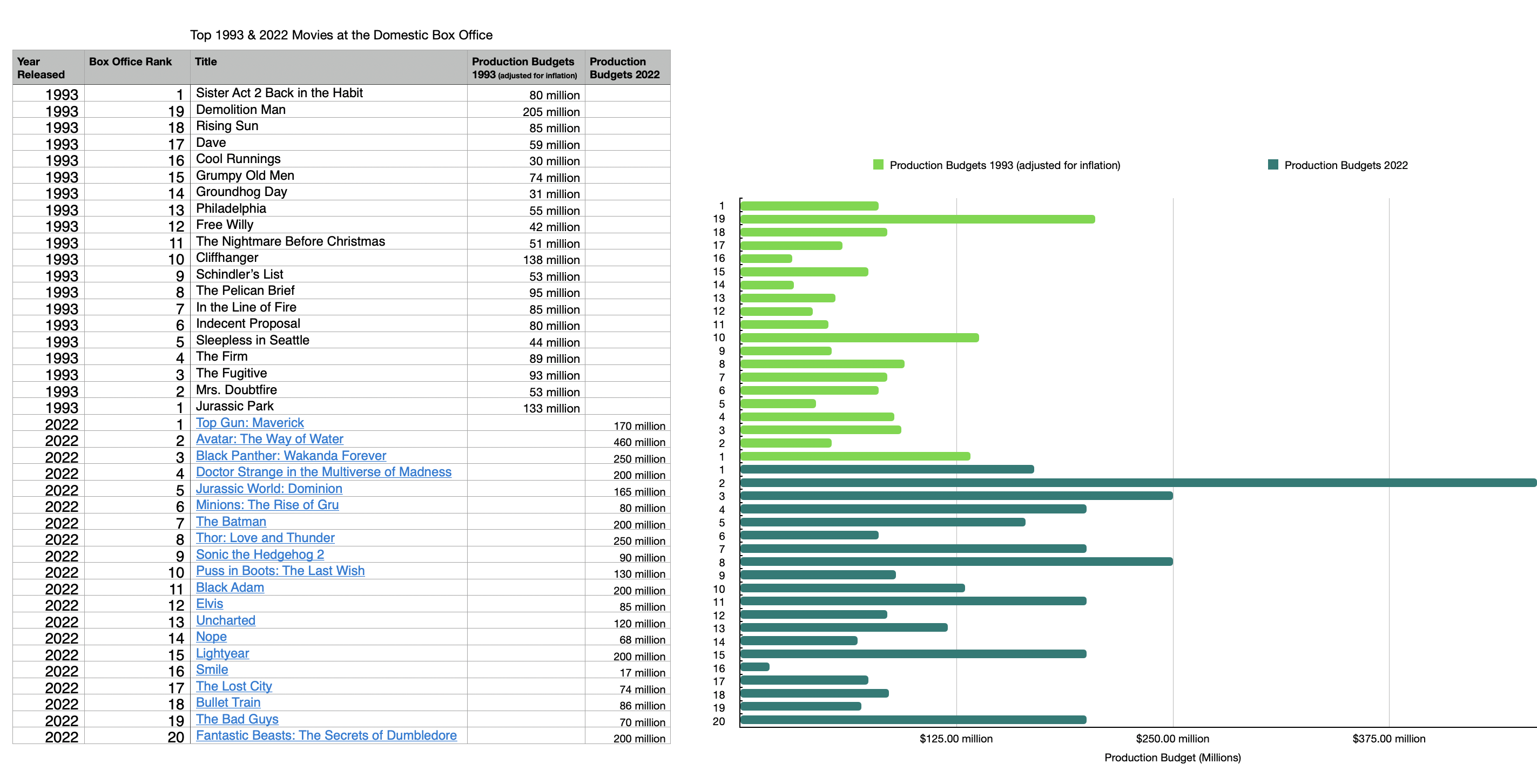

Scale, sometimes conflated to mean blockbuster or special effects, simply means production quality via its budget. Obviously, a hefty budget doesn’t directly equate to success. The correlation between a film’s budget and its success isn’t straightforward. Though high-budget films often perform well, this isn’t new, and it doesn’t stop low-budget films from succeeding. Conversely, big spending doesn’t shield a film from flopping.

Spectacle, is what film exhibition always was and will be. Though audience expectations of what stipulates a spectacle have changed, the medium has always been built around impressing viewers with something noteworthy and worth leaving home for. See King Kong, or a house falling on Buster Keaton for the oldest examples.

Below shows how much production budgets have changed, but also haven’t changed across 30 years.

Modern Market

Conditions of the Market

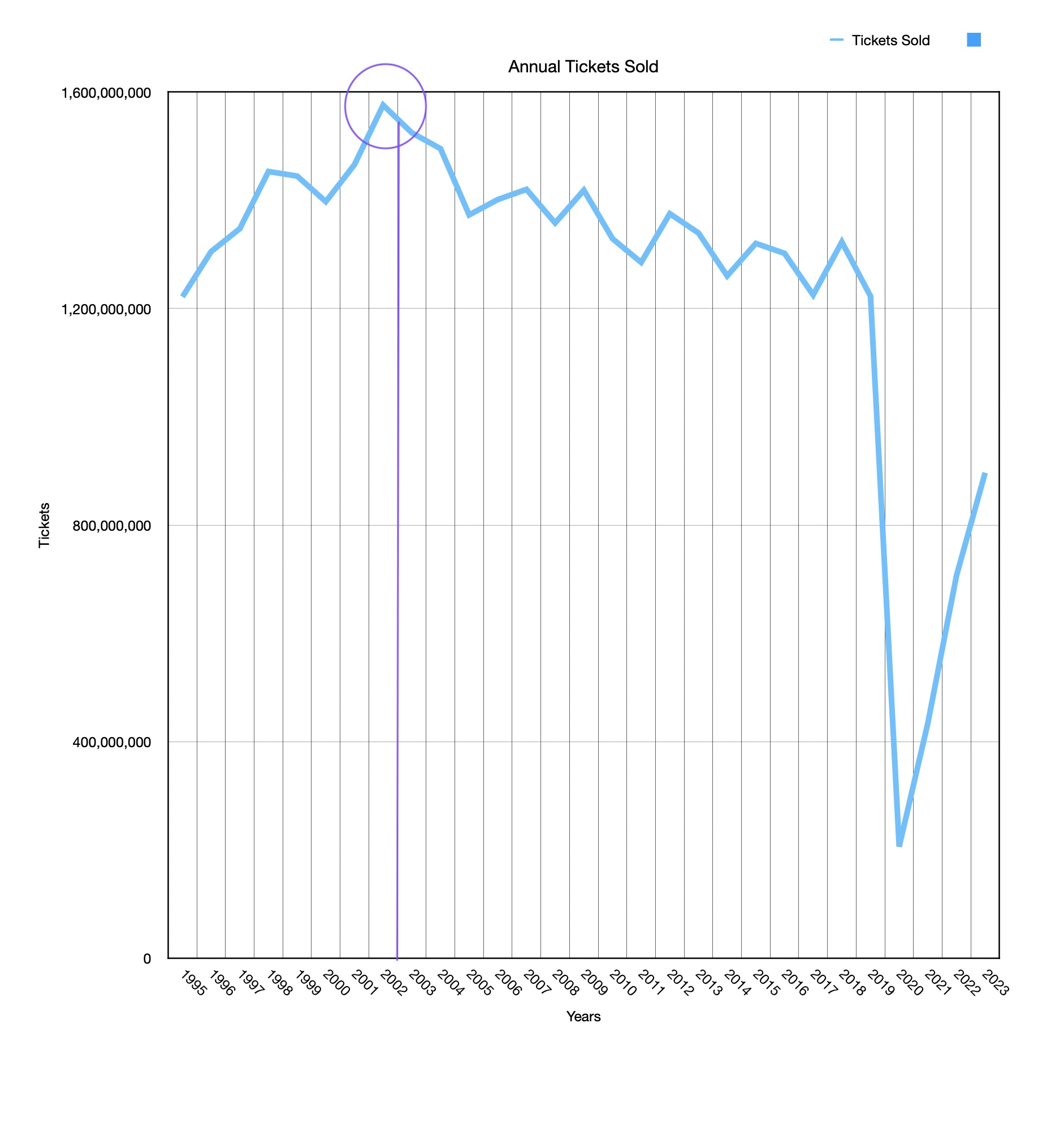

What makes the film business more challenging today isn’t anything fundamentally different about the business, but the conditions in which they operate. The reality is it’s much more difficult to get folks out to the cinema. It’s no longer the cultural default activity it once was. Ticket sales peaked in 2002, since then business has been on a downslope. Today, post pandemic, cinemas have established a new normal of low.

Annual Tickets sold by year - source The Numbers

Annual Tickets sold by year - source The Numbers

- General fatigue from digital lifestyles & bombardment.

- The saturation of available content

Short release to streaming timelines likely play a marginal factor as well.

Reaching Audiences is relevant too. Outside of fatigue and choice exhaustion, reaching audiences is a modern challenge too. What this means is baseline marketing costs need be higher for any exhibition campaign, regardless of production scale.

Given such challenges, a preference for the “reduced risk profile” of franchises seems almost logical.

Franchise Players

Franchises make the incentive structure more predictable & hence reliable. As mentioned before, there’s surely a cross priming that happens when you have different entries in a series. There’s also likely a marginal overlapping of marginal costs in the spiral up economies of scale.

And of course the secondary streams, the world building of franchises naturally lend themselves to cross modes of sales. TV, Video Games, MERCHANDISE, and theme parks.

Fast & Furious Coloring Book for Adults and Kids - sold at Walmart

Fast & Furious Coloring Book for Adults and Kids - sold at Walmart

What’s key to ear mark here is the film is always remain the primary drivers. At no point does the film merely become a vehicle for secondary streams, in the way thatnetwork TV does for advertising.

If a film does poorly, its merchandise lines, etc., will likely suffer as well. Star Wars laissez faire 2018 box office performance, followed by its likewise laissez faire merchandise sales is an obvious example of this.

And though franchises have largely become synonymous with superhero films they are very different. Any material runs the risk of suffocating, or annoying its audience. Star Wars & Comic Book films are testing the limits of this in live time. But—

Super Hero Fatigue ≠ Franchise Fatigue

See the Fast & Furious MasterClass for lessons on franchise pacing.

There might be more to be had by drawing your audience’s interest out over time, rather than bringing it all to the bank as quickly as possible.

Over a 22 year period, and 11 films, Fast & Furious grossed 7.3 billion globally via the box office. The Marvel Cinematic Universe over a 15 year period, and 45 films has grossed 29.5 billion globally.

If you divide film ∕ box office gross

• Marvel approximates to roughly $657 million per film • Fast & Furious approximates to roughly $665 million per film

Slow and steady wins the furious?

Some Predictions

Superheroes won’t last forever. Nothing lasts forever. There’s a limited viability in how much any rag can be wrung, or how long audiences will endure any genre tonality.

When superheroes evaporate, it’s speculative what will take their place in the market, but we can assume something will. It’s hard to imagine another spectrum of subgenre-rich franchise films will be it. Assuming that is true, we are likely at the ceiling of how many franchise films can fit in the market at one time.

Will theater turnout worsen. This is up for equal speculation. But assuming digital saturation is the primary driver in theatrical decrease, and assuming the 2002 turnout is the ceiling for theatrical turnout— we are likely at the relative floor. That is, also assuming the noise in society doesn’t increase.

Side Mission Prediction: if our culture ever develops a method to better manage our digital lifestyles (in decades or centuries?), the demand for the cinema would likely increase.

How does this bode for non-franchise films? The same as it ever was? Disney aside, most film studios don’t see it as good strategy to franchise EVERY film they release. Good strategy is to release a diverse array of carefully selected pictures. Including non-franchise films, good investments must be strategic & thoughtful, preferably with proven IP, or a director with growing acclaim.