Incentive Structure of the Television

What makes for successful television? What are the incentives for different platforms and the shows that run on them?

It’s worth exploring the broad strokes of each model, & historical + market relevance to see how they stack up. What are their respective constraints? What relationship is there between model and content?

Success in TV always boils down to viewership. Regardless of the platform—be it network television, premium, streaming, or other, value is determined by views. Incentives for the platform, the program creator, and advertisers, are always built around attention.

Viewership => Sales

Adventive of Incentive

At its onset, television was centered on value in exchange for ads.

At no cost to the viewers, advertisers could insert themselves directly into culture and public awareness, for the exchange of news or entertainment. For the viewer, the upfront cost was then, and still is today, the cost of a television with antenna signal reception. The ongoing cost, watching ads.

Sponsorship Model

“With a message from our sponsors”

In the beginning….. entire shows were backed by single advertisers. There were not spots like today, rather a program with a sponsor. And they were very much integrated.

Phillip Morris, the primary sponsor of I Love Lucy, would be mentioned nearly as many times as Lucy. Interruptions from our sponsors would present themselves directly into the show’s narrative like live commercials. Sponsors could even involve products of their choosing directly into the devices of program plots, a branded content dream come true.

Program Dynamic

Saying sponsors had a high degree of influence would be an understatement. One existed at the behest of the other. Creative approval was required for virtually everything on a show. For set design, actors, concept, music, props. Everything circled back to the sponsor, and how it reflects on the brand.

Briefly

Today, there have been fleeting instances of advertising that claim to be ‘a return to the single-sponsor model’. But this is namely Fox juicing out performance headlines. Despite the namesake, these runs are more akin to event-programming blocks in a spot model.

Spot Model

The feasibility of the sponsor model was limited, and was bound to run its course. The public’s tolerance for direct levels of advertiser involvement was waning. And with the increasing cost of show production budgets, the prospect of being a sponsor was losing its luster. Such gave rise to the spot model.

In the new attention economy, networks reasserted their own value, and slots became standardized into spots. More client involvement meant a diversity of revenue and a safer business overall. Standards and protocols became normalized, and abstract distance was created between programs, the network, the advertiser, and the viewer.

Early on, brands still held considerable sway over programming. Scripts were still subject to approval, and the enforcement of moral standards was a given. Eventually the granularity of control loosened over time, but advertisers have always maintained the ability to throw their weight around and voice input (if needed.) Creating shows that run parallel to an abstract universe in which the client lives, has always been the name of the game.

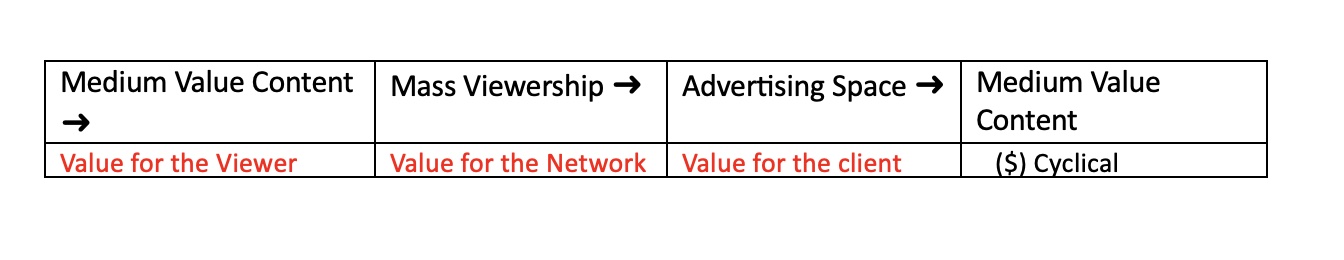

Principally, the spot model works within the same value scheme the sponsor model did, albeit fragmented and diversified. Entertainment in exchange for attention, with advertisement sprinkled in-between.

Cable Model

Medium to High Value Content ⇆ Mass Viewership ⇆ Advertising Space ($)➜

Medium to High Value Content ⇆ Subscription Cost ($)➜

In its debut, the cable model offered slightly edgier content segmented to more specific audiences. This is still mostly the case.

Cable channels are incentivized by both their paying viewers, as well as their paying advertisers. This has a mixed bag of costs.

For the subscriber, the cost of a cable package comes with a bundled package of channels. This has longtail benefits for both sides. Distributing specialized content broadly, negates the need for individual content to have broad appeal. This is the opposite of programming on network TV.

Dual Constraints

Dual revenue streams, in essence, means dual constraints. Offering ever so slightly edgier content had the initial effect of making viewers feel as if they were receiving something extra for their money. In today’s world, this association isn’t evident, but it’s not hard to see the content on FX or Comedy Central is edgier than that of ABC.

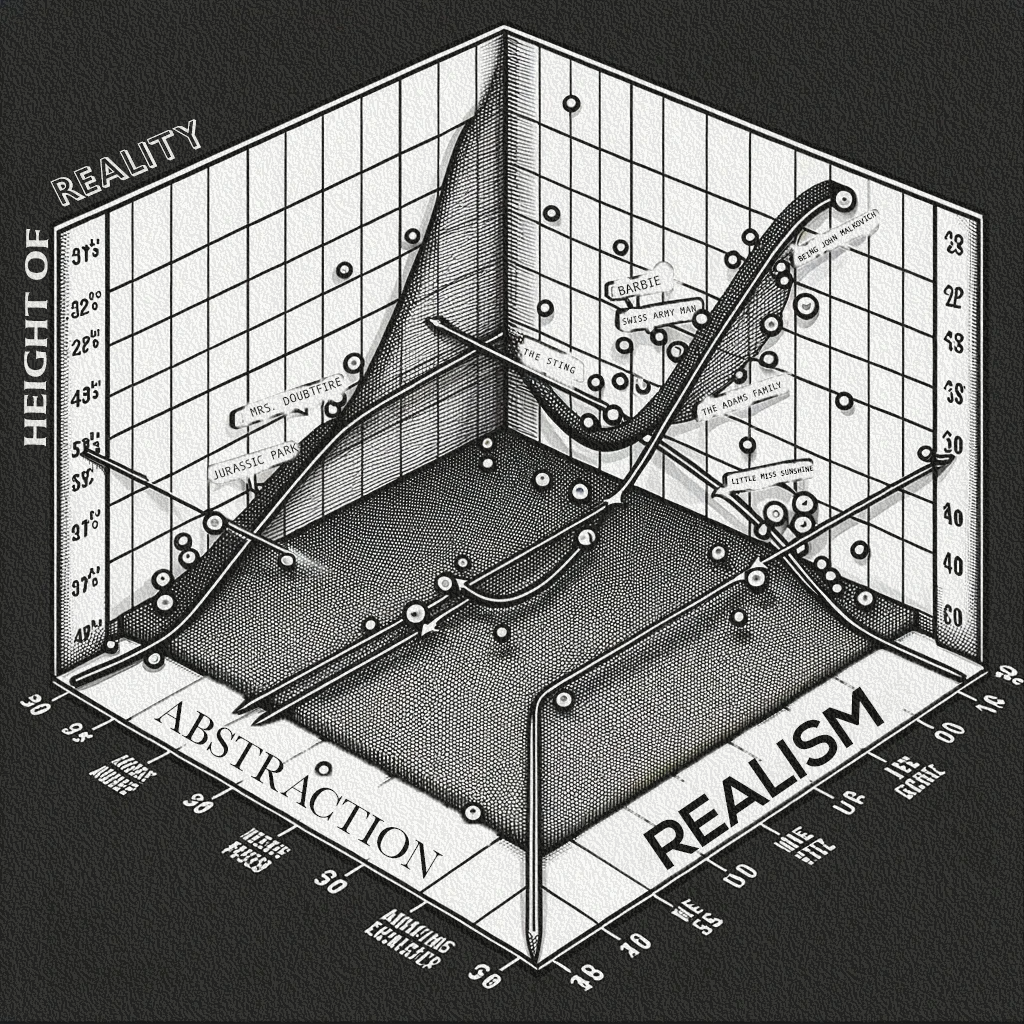

Cable channels still have, and had, moral boundaries to contend with, everything exists at the extension of the brand image in the scheme of things. Though FX is most notable today for pushing the envelope of acceptability, historically cable has had to exist in a family-safe continuum not much different than network. From the 70’s through the 2000’s they existed virtually in lone synchronicity as close points of differentiation, akin to varying shades of grey.

Cable content v. Network content

Programming

More diverse content, means advertising programming can select & slot demographics on the basis of who-type viewers & what-type shows. Airings of Star Trek, meant younger to middle-aged adults, ideal for anything sci-fi, or technology. ESPN generally means beers, cars, and sports brands pair well. “So forth, and so forth-“

Relationship to Advertisers & Content - Network & Cable

In this way, programs don’t exist at the behest of the advertiser, but the convenience. As long as both are of similar type, they can co-exist.

Hard Constraints - serving a purpose

This has the effect of shopping for content on the basis of programming. Is this something that works for this network demographic? Is this something that works for this time slot? If it meets that need, then it can be considered. Assuming a show meets those marks, it’s free to explore creativity within those constraints.

The relevance of programming schedules is largely diminished in today’s environment, but this is the precedent.

Soft Constraints - network notes

A seemingly endless amount of BTS and click friendly anecdotes detail the chagrin between showrunners and network notes. Despite the tendency to rage against convention, these conventions do have a purpose. They’re ongoing balance checks to ensure blocks maintain their programmatic friendly appeal. Undoubtedly, there’s some procedural entrenchment at play here as well, making for particularly dull TV. But given the state of current linear TV, these checks have likely lightened up in recent years, especially in cable domains.

Premium Cable

Compared to prior television models, premium television is unadulterated and direct. It’s akin to getting milk from the udder, before its tainted by advertisers.

High Value Content ⇆ Subscription Cost ($)➜ cycle

When compared to cable & network, premium services give the viewer something extra for their buck. A sense of exclusivity, previously not available through normal channels. At its start, premium’s differentiation was its host of titles available for home viewing. This shifted to include content that had a focus on sports, live events, documentaries, unscripted, and adult. Historically HBO led the front here. As of the 2000s premium providers became notable for their convention defying takes on scripted content, as well as their high budgets doing so.

These specialty items are only incentivized to exist in a direct exchange model. Fee for cost.

A shared model like cable, with the interests of advertisers, is too much to contend with for any form of content that doesn’t return immediate demand. Long term documentaries, or narratives that take multiple seasons to hit their flow don’t fit well into that equation.

Interestingly, the viability of both Showtime and HBO very much relied on network television to exist as a stark point of differentiation. Since the decline of TV in the 2010s that line, and hence value has become blurred.

Netflix Horizon

High Value Content ⇆ Subscription Cost ($)➜ cycle — For all the hoorah editorialized about Netflix at its outset, it has essentially operated along the same incentive chain as previous premium providers before it. Subscription cost in exchange for content. What made it different, was its delivery method. The most interesting thing about Netflix is that it effectively transformed from being a utility service(rentals) to an actual content provider. Via a first mover advantage + an aggressive growth strategy, Netflix reached scale comparable to its legacy peers, with cashflow turning positive in 2021.

Relationship to Content

In its infancy, Netflix stated its looking to do what HBO does, but better. Its only hard constraints is subscriber appeal, its soft constraint— content strategy. [JP1]

Netflix leans hard into data here. Famously it pursued House of Cards, because audience metrics signified a demand for political dramas + David Fincher + Kevin Spacey. In more recent years its programming prompted criticism for spontaneous add + drops. The suggestion is that Netflix’s content strategy happens in a void.

This sensation of a void may be accurate. Netflix seems to lack channels for personalized feedback from users or press, and it prefers that to which it can quantify, algorithmic data. It’s not known for disclosing its decision making process, although some users seem to expect this.

But it’s not a void without strategy, just without feel. Data & demographic strategies are at the forefront of not just programming, but corporate moves and Netflix culture at large.

Streamers

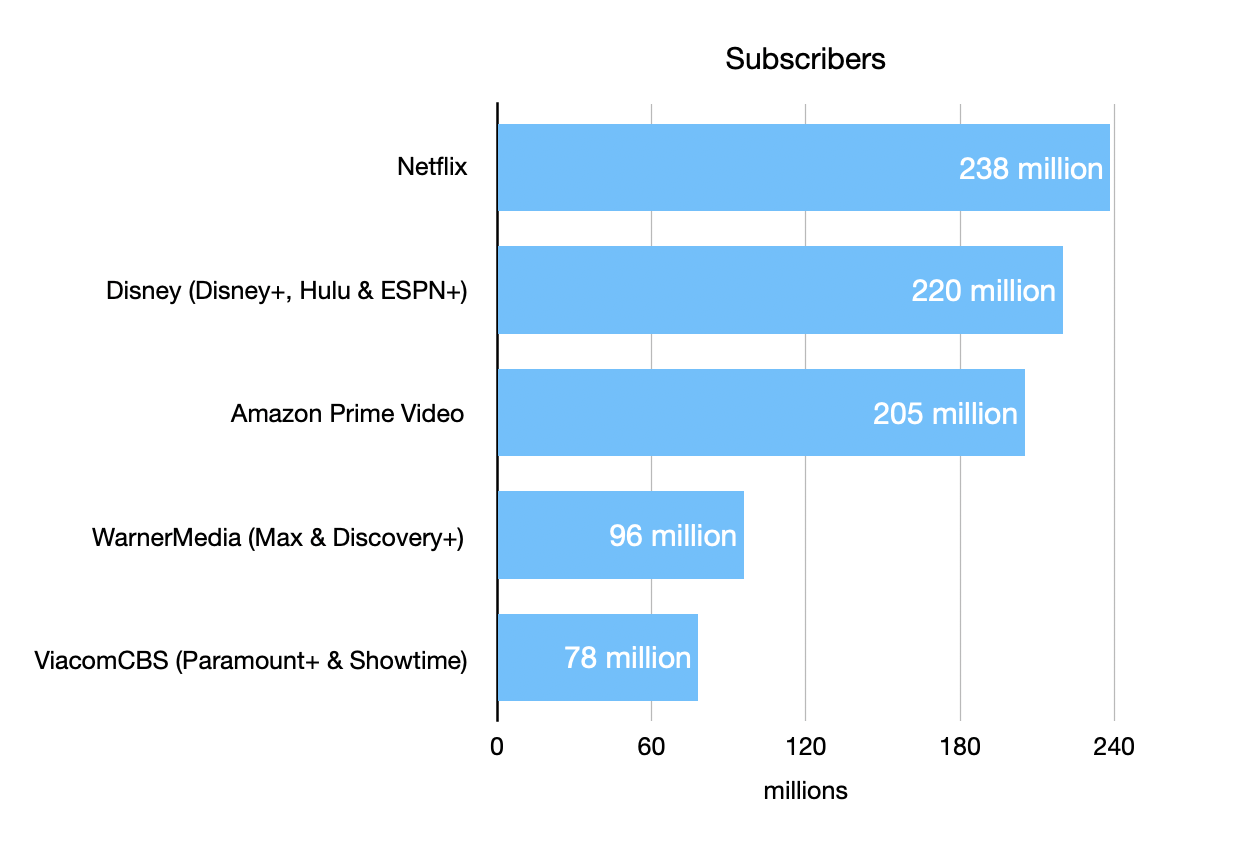

Since the Netflix horizon, the old world has become the new world. Of the top five streaming platforms, three are legacy conglomerates, the exceptions being Netflix and Amazon.

Ad Lite - Streamers

Premium Value Content -> Subscription Cost -> Viewership ($)➜

Premium Value Content -> Less Subscription Cost -> Viewership ⇆ Advertising ($)➜

In 2021, Netflix began adopting Nielson as a means to make itself more desirable to advertisers. In a streaming environment initially predicated upon no commercials, all major platforms have since adopted the commercial tier option.

To date, commercial blocks, don’t function as a viable revenue service for ANY major platform. But growth predictions are significant across the board.

What this means for content

The Ad Lite model is seemingly similar to the cable model, but differs in that advertising provides much less revenue. The subscriber is always the primary incentive here. Even in its ad-lite tier, ad space operates under the constraint— it exists only at the leisure of subscriber spending. Anything lest, and there’s jeopardy.

Conversely advertisers have much less sway over content, when compared to the old cable model. Streaming does allow room for BTS & extras, and product placement is still living its branded content dream. But ultimately this is fluff, and has little effect on the content itself.

Double-conversely, advertisers view ad-lite programming much less favorably. Compared to cable at its peak, ad lite leaves a lot to be desired. Ad Lite streamers allegedly allow for more data based profiling and targeting, but the gross impact of its viewership frequency pales to previous generations. This is likely due to the larger spread of content overall, as well as overall fragmentation.

Niche Providers

Narrow niche focus -> Subscription Cost ($) ➜

Niche streamers bring in audiences because of specific genre focuses. They are not too dissimilar from genre based cable channels (which emerged in cable’s latter years.) In contrast, large platforms have a much more generalist berth of content, than say the 500+ horror movies Shudder carries.

Demand for niche content definitely exists with subscriber counts ranging from 25 million to the hundreds of thousands for different platforms.

Curiosity is likely the peak with 25 million subscribers, if you don’t count sports platforms, which you shouldn’t. Many seem to be living in the low millions range with Britbox at 3 million, Mubi at 12 million, and Accorn at 12 million. Several, such as Criterion, don’t disclose their subscriber count.

The challenge is to appease enough narrow demand to sustain operational costs, without widening appeal so much that it undermines unique draw.

For simplicity, niche streamers can be broken into 2 categories.

- Independent stand-alone platforms - such as Curiosity, Mubi, or Fandor

- Subsidiary platforms - such as Britbox, Shudder, or Crunchyroll

Content Flow

The content relationship here is largely about acquiring what fits and is affordable. Deal flow likely resembles, find what’s available, and what’s already been discarded by the larger players. Namely low box office movies, and the plethora of TV shows out there in the universe that all have low demand. This workflow harkens back to the days of cable channels needing to fill a lineup..

In addition to being squeezed down from the top, niche streamers are also being crowded up from the bottom by Freevee-like platforms.

Less than ideal

AMC has thus far survived via a shrewd deal work of licensing properties and platforms smaller than itself. Somewhat like the major streamers, but much-much smaller. The constraints for any niche provider are far from ideal, and it’s hard to imagine a wiggle room of excess.

Per David Zaslav (of Warner Discovery) the universe is moving towards a black hole of super bundling, though those aren’t his exact words.

But, despite constraints, independents are operating with some viability, even if its lean viability. Minor amounts of subscriber decreases within the last year can likely be attributed to market conditions, rather than platform failures. Rightnow Media (“a peculiar” b2b Christian platform), Mubi, Curiosity, and Criterion are all generally moving positively, and seem to have found a mixed bag of strategies that work.

Freevee Model

Free –> 4 -<– vee

Viewership -> 4 <- Viewership

The other streaming model worth mentioning, is the “Freevee” model, referred to by those in media as FAST (Free, Ad-Supported Television.) Freevee, rolls off the tongue easier. It includes Pluto, Tubi, Roku, Xumo and Freevee, among others. What’s most interesting about this model is how reminiscent it is of early day network television. It is entirely based on generating value to advertisers via free viewership. Radio 3.0.

It makes sense most FAST platforms are legacy owned, as they are looking for an avenue to maximize idling content that isn’t being premium’d elsewhere. Roku is the exception here, an independent wielding a first mover advantage, there are also some hardware contingencies at play.

In terms of sheer growth, Freevee-like platforms are having a FAST boom. High growth is likely for the next couple years. That said, their total subscriber numbers are still fractions of dominant players.

YouTube Model

It’s not TV, it’s You

Segmented Content -> Viewership -> Ad Dollars

Value to the Audience -> Value to the Platform -> Value to the Advertiser

It’s impossible to discuss modes of television without including YouTube into the forum. On one hand YouTube operates in a modality part social media, and on the other it offers what TV has always offered: entertainment. Unlike traditional TV, or even major streamers, YouTube is able to offer a special kind of segmentation. Segmentation that can only be appealed to via micro production outfits, anything too large, and there’s a risk the message becomes lost.

This isn’t to say, that scaled production doesn’t have a place on YouTube, it does. But it’s content that’s recycled from other mediums. The content YouTube hosts exclusively, can really only exist & thrive on its own platform.

YouTube differs from social media peers TikTok and Instagram in that it offers long form content.

But like social models it generates value by capturing dual forces. People who want to create, and people who want to consume. The more segmented, the more specialized, the better.

Micro Productions

There’s more to be said about the production quality of YouTube’s micro producers. There’s a deft of clarity at play here. In many instances should scale be applied, clarity is lost, and if not clarity viewer appeal. Take the umbrella category of infotainment, a YouTube user with video editing skills, writing skills, and an editorial eye can provide subject coverage that gets to the heart of a matter.

To be more specific, an investigative story produced by cable outfit such as A&E, can be made to hit any runtime needed. Throw in some excess B camera coverage, excess sound design, excess witness statements, and some fritless B narrative speculation and you have the formula for fluff.

Whereas a YouTube producer, for less production spend, can hit this same story in a way that’s likely more astute, and speaks to their own editorial instincts. The latter based solely on public access material.

This comparison in quality per production capita isn’t limited to investigative stories, or even infotainment. There’s a spectrum of content at play on YouTube, that can only be satisfied via small scale.

Constraints: Separate but Separate

YouTube operates in dual revenue modes, what’s impressive is how little effect each mode has on the other. Whereas the cable subscriber can always feel the taste of ad influence on their tongue, YouTube viewers are by and large segregated from one another.

Ad influence still exists in the YouTube model, but maybe it’s less relevant in this format. Via a gross uniformity of rules YouTube is able to create an environment suitable for advertisers and subscribers simultaneously. Enforcement primarily focuses on maintaining IP standards and ensuring content remains within a TV-14-like framework. This enforcement is mainly achieved by the threat of demonization.

Demonetization is a mechanistically brilliant move on the part of the platform, rather than bar content outright and become embroiled in granular levels of regulation, demonetization allows the sharing of content, something that still net benefits the platform, albeit on a secondary level. This also allows the creator to still participate in the purported appeal of sharing ‘what you make’, albeit in a neutered way.

With 80 million subscribers, YouTube exceeds that of streaming platforms Paramount, Peacock, Starz, and Apple. (This number doesn’t included its free ad-based users.) YouTube does this without the production and acquisition modes of its peers.